Bassett Hall Garden Irrigation System Archaeology: Summary Report

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1714

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2002

Bassett Hall Garden Irrigation System Archaeology

Summary Report

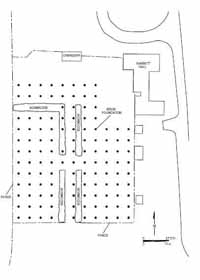

Between April 8 and 11, 2002, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research (D.A.R.) conducted a close interval archaeological shovel test survey of the garden area located to the west and southwest of the Bassett Hall dwelling house (Figure 1). The house and garden are both located on Block 1, on the south side of Francis Street, within Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. The purpose of the survey was in order to identify the nature and extent of any potential archaeological resources within the garden that may be impacted by the installation of a new garden irrigation/sprinkler system.

Figure 1. Shovel test locations at Bassett Hall garden.

Figure 1. Shovel test locations at Bassett Hall garden.

The archaeological survey consisted of the excavation of a total of 121 round shovel test pits (STPs) systematically placed at 5-meter intervals across the area of the garden. The garden was bounded to the north by the orangery and a fenceline extending to the east and west from the orangery; to the east by the main dwelling house and the three outbuildings extending south from the house; to the south by an east-west fenceline; and to the west by a north-south fenceline. The total area of the garden measured 65 x 55 meters or approximately .88-acres. Each shovel test pit was excavated to undisturbed subsoil, and detailed descriptions of the stratigraphy were recorded, including soil thickness, soil type, and soil color. All excavated soils were passed through ¼-inch mesh screens to recover artifacts for laboratory analysis. At the laboratory, all the artifacts were washed, numbered, and inventoried. All of the field and laboratory documentation, in addition to the artifacts recovered during the survey, are stored at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research Lab.

Historical Background

In the seventeenth century, prior to the founding of Williamsburg, the area encompassing Bassett Hall was part of a 290-acre tract of land purchased by James Bray in 1671. At the time of Bray's purchase, the tract was part of a small inland community known as Middle Plantation that had been established in 1632/33. After Bray's death in 1691, his wife and children inherited the property (Stephenson 1963:2-4). Several years later, in 1699, the colony's capital was moved from Jamestown to Middle Plantation, and the area was renamed Williamsburg. As part of the establishment of Williamsburg, a portion of the Bray estate was annexed for the new capital.

In the first half of the eighteenth-century, the remaining portion of the Bray estate descended through several generations of male Bray heirs, until Elizabeth Bray Johnson inherited the estate from her father, Thomas Bray II in 1751 (Stephenson 1963:17). Recent archaeological investigations of the Bassett Hall dwelling house suggest that the original portion of the house may have been constructed during Thomas Bray II's ownership of the property (Kostro 2002:42). Elizabeth Bray Johnson died in 1765, and the estate was then held in trust for the benefit of her children, although her husband, Philip Johnson, was entitled to a life right of her property. After his wife's death, Johnson evidently did not live in the house, and instead rented it out to tenants. Johnson died in 1789, at which time the property was probably placed up for sale (Stephenson 1959:412).

By 1794, the estate was sold to Richard Corbin of "Laneville", who carried out extensive repairs to the main dwelling house between 1794 and 1795. Soon after the repairs were completed, Corbin sold the house and property to Burwell Bassett of Eltham, from whom the property eventually would draw its name from. Following a long-standing family tradition, Burwell Bassett was actively involved in government, serving variously as a member of the House of Delegates, as a Congressman, and as a Senator. Bassett lived at Bassett Hall until 1840, when it sold to another politician, Judge Abel Parker Upshur, who served as Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of State under President John Tyler. 3 Upshur, however, only held the property only briefly, selling it to John Coke in 1843. Coke in turn sold it to Goodrich Durfey in 1845 (Stephenson 1959:12-19).

Goodrich Durfey and his family lived at Bassett Hall from 1845 until his death in 1869. In 1870, Israel Smith purchased Bassett Hall from the executors of Durfey's estate. Smith died in 1879, at which point the property was passed to various members of the Smith family. The Smith family retained ownership of Bassett Hall until 1927 when it was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg (Stephenson 1959:19-20). Renovations to the main dwelling house were completed in 1936, after which the house was maintained as the private Williamsburg residence of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. The Rockefeller family donated Bassett Hall to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1979 (Blackford et al. 1984).

Results of Shovel Testing

The shovel test survey of the Bassett Hall garden revealed a relatively uniform soil stratigraphy across the project area, reflecting a profile resulting from the agricultural plowing and landscaping of the area encompassing the garden. In general, the soil profile consisted of a 10 to 20-cm thick silt loam topsoil, over a 20 to 30-cm thick sandy silt loam plowzone, over sandy clay subsoil. In some cases, a 10-cm layer of silty clay loam fill was also identified between the topsoil and plowzone layers --likely the result of landscaping across the garden in order to level the grade. In addition, shovel tests in the northwest portion of the project area, and closer to the orangery, tended to be deeper in depth.

Although the majority of the shovel tests within the garden area followed the above- described stratigraphic profile, significant ground disturbance was identified along the parallel rows of boxwood planting beds that extend south from the orangery and through the center of the garden. Shovel test within the planting beds revealed that the planting holes for the boxwoods were wide and deep, displacing the plowzone and extending deep into the subsoil to accommodate the large root balls of the boxwoods. Evidently, the boxwoods were grown outside of the Williamsburg area, as attested to by the distinctive red-colored dense clay of the planting fill. Most likely, the boxwoods were grown in a nursery and were subsequently transplanted to Bassett Hall once they reached a desired age or size. Not found anywhere within the Tidewater, similar red clays are found in the Piedmont sections of Virginia and North Carolina, suggesting that the boxwoods were grown in that region. Boxwood planting holes with red-clay fill were also noted around the perimeter of the Bassett Hall dwelling house during archaeological excavations of the house in 2001 (Kostro 2002:70). The significance of the boxwood plantings is the total destruction of the archaeological record within these planting beds.

With the exception of the boxwood planting beds, most of the rest of the project area is undisturbed in modern times, save for a few narrow utility trenches through the garden for the existing garden irrigation system. Eighteenth and nineteenth-century artifacts were recovered from almost every shovel test across the garden. Artifacts recovered during the 4 survey included domestic or household refuse such as various ceramics, wine bottle glass, and animal bone. Architectural debris was also recovered from the vast majority of the shovel tests, consisting primarily of nails and nail fragments. Window glass was also recovered, but in a substantially lesser quantity. The presence or absence of brick fragments was also recorded for each test — the vast majority of which did contain some brick.

Interestingly, distinct concentrations of whole bricks and brick bats were noted in two distinct locations. At N950/E1530, directly south of the orangery, four large handmade brick bats were recovered from the plowzone at depths exceeding 50cm. In addition, the brick bats were found in association with a heavy concentration of nails, as well as, a concentration of flat iron fragments. The concentration of bricks and artifacts may suggest that a structure may have been located at this location. Alternatively, this concentration of bricks and artifacts may indicate that this was an area of trash disposal.

A second brick concentration was noted at N930/E1550, where the excavation of the

topsoil and a layer of fill exposed a pile of brick rubble located at 30cm below modern

grade. A large quantity of eighteenth and nineteenth-century artifacts including ceramics,

glass, nails, and animal bone was also recovered from the layer of fill above the bricks.

Directly to the north of the shovel test with the brick rubble, the excavation of the shovel

test at N935/E1550 exposed a small intact brick foundation located at a depth of only

20cm below modern grade, buried under a layer of fill containing a large quantity of

eighteenth and nineteenth-century artifacts (Figure 2). The bricks appear to have been

Figure 2. Brick foundation at N935/E1550.

5

handmade, and are typical of those found on eighteenth-century archaeological sites

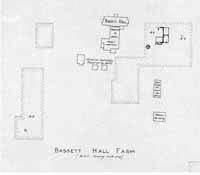

throughout Williamsburg. Significantly, the location of the brick foundation corresponds

with the locations of several small "colonial outbuildings" located southwest of the main

dwelling house as indicated on the 1932 Archaeological & Research Key Map of the

Restoration Area, Williamsburg, Virginia (Figure 3). These buildings, which include a

smokehouse, dairy, and kitchen, which were evidently moved from the garden area to

their present location to the rear (south) of the main dwelling house in 1931 (Whiffen

1987:260). Most likely, the brick rubble found to the south of the foundation represents

additional architectural debris associated with the removal of these structures. These

structures, however, do not appear on the Desandrouins Map (c.1781) or the Frenchman's

Map (c.1781), suggesting that they were constructed at a date after the maps were

produced.

Figure 2. Brick foundation at N935/E1550.

5

handmade, and are typical of those found on eighteenth-century archaeological sites

throughout Williamsburg. Significantly, the location of the brick foundation corresponds

with the locations of several small "colonial outbuildings" located southwest of the main

dwelling house as indicated on the 1932 Archaeological & Research Key Map of the

Restoration Area, Williamsburg, Virginia (Figure 3). These buildings, which include a

smokehouse, dairy, and kitchen, which were evidently moved from the garden area to

their present location to the rear (south) of the main dwelling house in 1931 (Whiffen

1987:260). Most likely, the brick rubble found to the south of the foundation represents

additional architectural debris associated with the removal of these structures. These

structures, however, do not appear on the Desandrouins Map (c.1781) or the Frenchman's

Map (c.1781), suggesting that they were constructed at a date after the maps were

produced.

Figure 3. 1932 Archaeological and Key Map showing colonial outbuildings

southwest of Bassett Hall.

Figure 3. 1932 Archaeological and Key Map showing colonial outbuildings

southwest of Bassett Hall.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The systematic close interval archaeological shovel testing of the Bassett Hall garden yielded significant results regarding the use and occupation of the garden. A distinct 6 plowzone layer was found across most of the garden area, indicating that the area was at one time a plowed agricultural field. In addition, the layer of fill between the plowzone and topsoil layers identified in some of the tests suggests that the ground surface may have been deliberately built up as part of the landscaping of the garden. Significantly, a wide scatter of domestic and architectural debris, dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was recovered from the plowzone and subsequent fill layer from a large majority of the shovel tests extending all across the garden. The only significant ground disturbances detected was along the existing boxwood planting beds. Shovel tests within the planting beds indicate that the planting and replanting of the boxwoods, among other trees and bushes, along these beds has completed disrupted any intact subsurface archaeological features or deposits.

The survey also identified an intact portion of a small brick foundation, probably associated with one of the outbuildings that were relocated from the garden during the restoration of Bassett Hall. The foundation bricks, and the artifacts found in association with the foundation, suggest that the foundation probably dates to the eighteenth-century. A map of the property further corroborates this conclusion. A concentration of brick rubble south of the foundation may be additional debris associated with the removal of the building, and a second concentration of brick near the orangery may indicate the location of yet another building, or possibly that the area was used as an area for refuse disposal.

In conclusion, the results of the archaeological survey clearly indicate that intact archaeological features remain preserved within the area of the garden, and would likely significantly contribute to the understanding of the historical development of the Bassett Hall garden and house lot. As a result, the plans for the new garden irrigation/sprinkler system should be designed in order to avoid any known archaeological features, in particular, the brick foundation. In addition, any excavations required for the installation of a new garden irrigation/sprinkler system should be monitored by an archaeologist in order to document any additional, as yet undetected features, that may be exist within the garden.

Bibliography

- 1984

- Bassett Hall: The Williamsburg Home of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 2002

- Archaeological Excavations of the Bassett Hall Waterproofing Project, Williamsburg, Virginia. Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Reports, Williamsburg, Virginia. 7

- 1959

- Bassett Hall Historical Report, Block 1, Building 22. Manuscript on file, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1987

- The Eighteenth-Century Houses of Williamsburg: A Study of Architecture and Building in the Colonial Capital of Virginia. Revised Edition. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.